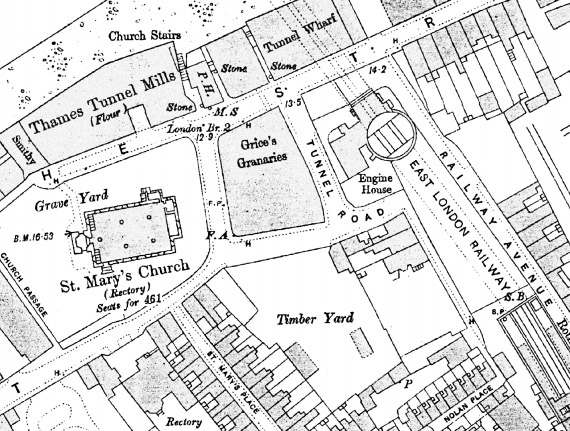

Botchergate, Carlisle (MAP: OS Town Plans 1:500 – published in 1865)

Botchergate, Carlisle (MAP: OS Town Plans 1:500 – published in 1865)

Thirteen years after Sir Rowland Hill, Secretary of the Post Office, introduced the Penny Post that the first mainland Pillar Box was erected in Botchergate, Carlisle in 1853.

The advent of the British wayside letter box can be traced to Sir Rowland Hill and his Surveyor for the Western District, and noted novelist, Anthony Trollope (known for The Warden, Barchester Towers and the Palliser novels).

Before 1853 it was customary to take outgoing mail to the nearest letter receiving house or post office, where the Royal Mail coach would stop to pick up and set down mail and passengers. People would take their letters in person, or in some areas they could await the appearance of the Bellman. The Bellman wore a uniform and walked the streets collecting letters from the public while ringing a bell to attract attention.

In 1852 Anthony Trollope was sent by Rowland Hill to the Channel Islands to ascertain what could be done about the problem of collecting the mail on the islands. To post a letter in Jersey or Guernsey, the post had to be taken down to the quayside and handed to the Master of the Royal Mail steamer in person. This was a somewhat inconvenient practice, subject as it was to the uncertainties of weather and tides.

Trollope’s recommendation back to Hill was to employ a device he had probably seen in Paris: a “letter-receiving pillar”. The first pillar boxes was brought into public use on Jersey in late November 1852 and they were an instant success.

By the next year the idea had spread to mainland Britain, with England’s first pillar box erected at the corner of Botchergate and South Street in Carlisle. In basic form all boxes were vertical cast iron ‘pillars’ with a small vertical slit to receive letters, but by 1857, after experimenting with various designs, horizontal, rather than vertical, slots were taken as a standard. The Committee responsible for the standardisation designed a very ornate box festooned with Grecian style-decoration but, in a major oversight, devoid of any posting aperture, which meant the slots were chiselled out of the cast iron by local craftsmen, usually destroying the look of the box.

Prior to 1859 colours varied until a bronze green colour was chosen as the new standard, which was to last until 1874. Initially it was thought that the green colour would be unobtrusive. Too unobtrusive, as it turned out — people kept either walking into them or past them. Red became the standard colour in 1874, although ten more years elapsed before every box in the UK had been repainted.

Find out about the history of your area. Visit Cassini Maps

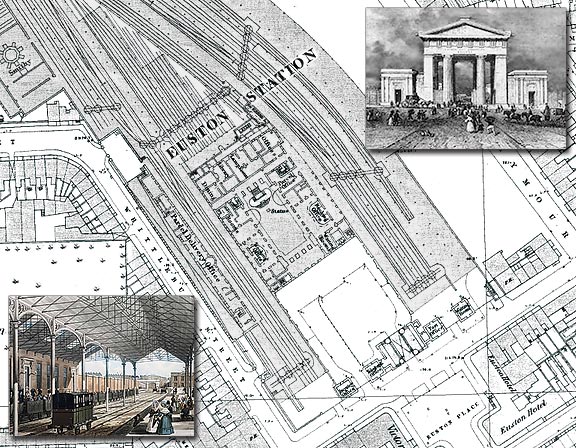

There was a notable engineering oddity about Euston from its opening on July 20 1837: because Lord Southampton, master of the Quorn Hunt, Conservative grandee, and a major landowner locally, objected to the potential noise and dirt, no locomotives were allowed between Euston and Camden Town. Instead trains were pulled from the terminus to Camden by a cable device until 1844, when engines were at last allowed.

There was a notable engineering oddity about Euston from its opening on July 20 1837: because Lord Southampton, master of the Quorn Hunt, Conservative grandee, and a major landowner locally, objected to the potential noise and dirt, no locomotives were allowed between Euston and Camden Town. Instead trains were pulled from the terminus to Camden by a cable device until 1844, when engines were at last allowed.